Table of Contents

Vive the Grand Paris Express! (But Let's Not Forget the Original Métropolitain)

PARIS'S Métro system, that baby of the belle époque, will celebrate its 125th birthday in 2025. With its 50 miles of corridors, its 141 miles of tracks and its 308 stations – including the cavernous Châtelet-les-Halles, considered the world's largest public transit station – the Métro is a parallel, underground city, one that is as deeply embedded in the French psyche as it is in the limestone and gypsum of Paris itself.

Before that anniversary, though, the next phase in transit—in the city where the whole concept of public transportation was invented, by philosopher Blaise Pascal, in 1662—will be born. The Grand Paris Express, a 120-mile system that will add four lines and 68 brand-new stations to the network will begin operations in 2024, in time, if all goes well, for the Summer Olympics. The system will serve the suburbs, with driverless trains platform doors, and it is bound to be as shiny and impressive as the last-born of the lines (Line 14, the automated Météor), was when I first rode it on the hundredth anniversary of the métro, in 2000.

I’ll dig deeper into this paradigm-shifting system in upcoming Straphanger dispatches, but before I turn to the future, I want to linger a little over the past. The Parisian Métro was the first urban rail system I really mastered—as an English teacher in the 1990s, I rode all over Paris and its banlieue to give lessons to doctors, high-school students, and accountants.

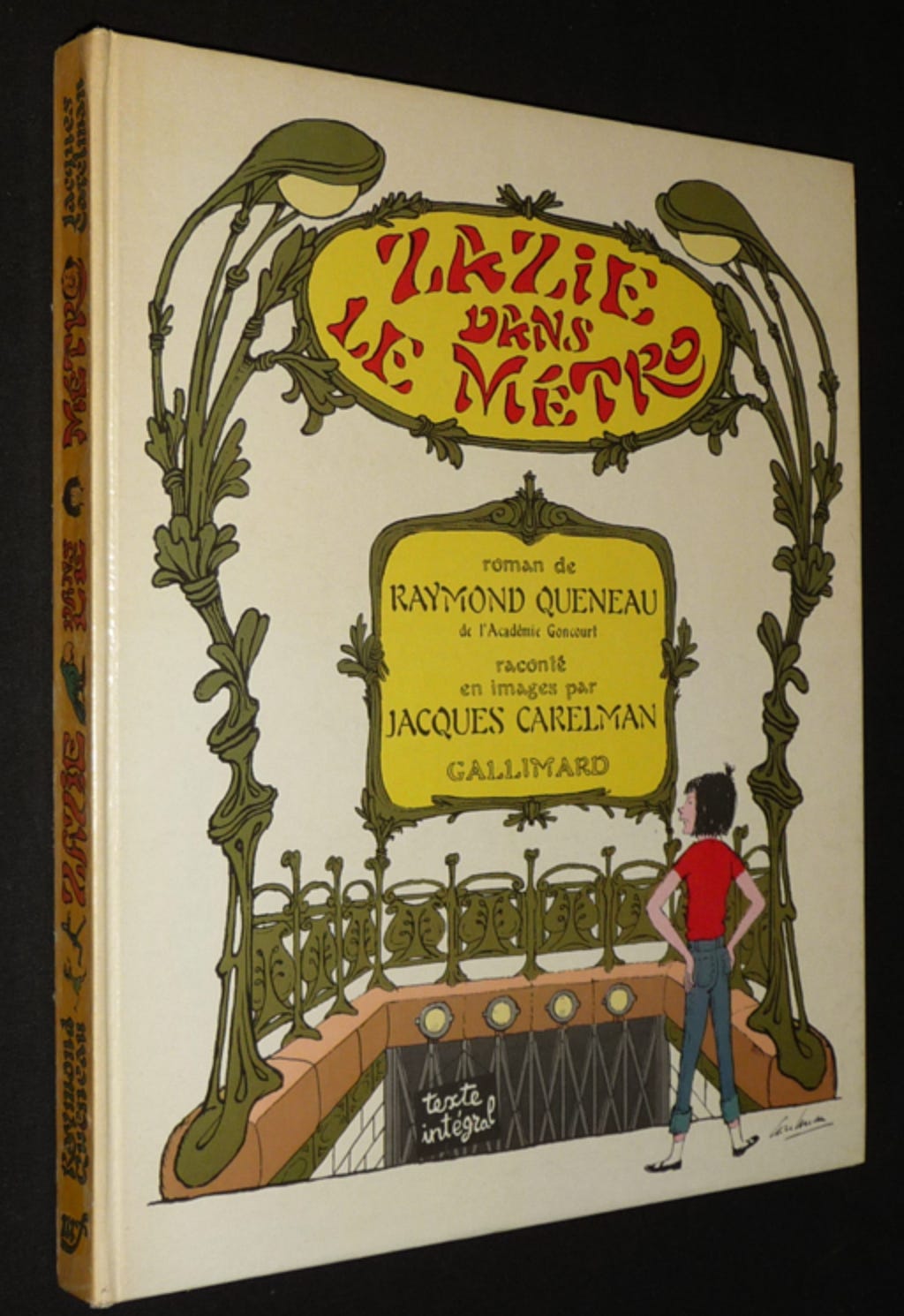

The Parisian Metro, certainly one of the most elegant transit systems in the world, is also surpisingly affordable (a single ticket is €2.10, or €1.69 a ride if you buy a carnet of ten). It is also the most ubiquitous (you're rarely more than 550 yards from a stop) and among the safest. I have a profound nostalgia for the Métro I got to know in my twenties— that Chanel-and-Gauloise-scented labyrinth of murky tunnels, with its tumescent Art Nouveau entranceways, its gray mice scampering beneath the rails and its gypsy accordionists. The same Métro that Zazie, thwarted by one of the system's recurring strikes, failed to see in Louis Malle's cinematic adaptation of Raymond Queneau's supremely playful 1959 novel Zazie dans le Métro. The Métro that Louis-Ferdinand Céline cited as his inspiration, claiming that “I owe the revelation of my genius to the Pigalle station,” his famous ellipses…peppered throughout such novels as Death on the Installment Plan…corresponding to narrative rails along which the “emotional Métro car” of his story clattered. The official history of the Métro is fascinating, but what I’ve always been drawn to are the lesser-known secrets of the subterranean kingdom.

The troubled birth of the Metro, for example. While work on the London Underground began in 1860, and New York had a steam-powered system of elevated trains by 1871, Parisians spent most of the 19th century hailing three-horse double-decker omnibuses, which averaged less than 5 miles an hour in the already traffic-clogged streets. Early plans included those in which above-ground Métro cars would be lifted by elevators and then allowed to coast to the next station under their own weight, and trains that would follow sinuous tracks on raised pylons in the middle of the meandering Seine. The idea of a Métro aerien, whose elevated tracks would surely have ruined the views of Notre-Dame and the Louvre, was strenuously and successfully opposed by Victor Hugo and the Société des Amis des Monuments Parisiens.

The current, mostly underground system, inaugurated on July 19, 1900, in time for the World Exposition, was built by 3,500 workers who froze the ground to drill beneath the Seine, sank sections of prefabricated tunnel into the riverbed and ripped up paving stones, turning boulevards into vast open wounds. The Métro was quickly adopted by Parisians, becoming an alternately adored and reviled -- but ultimately inescapable -- feature of French collective consciousness.

Salvador Dalí, not exactly a model of graceful progress into old age, proclaimed that any man still riding the Métro at the age of 40 was a raté, a loser. (But: see above.) After the May 1968 student demonstrations, “Métro-boulot-dodo” (“subway, job, beddy-bye”) became a rallying call to express frustration at the stultifying routine of urban existence. Gradually, the Métro came to represent the obscure id -- authentic, workaday, but seedily intriguing -- beneath the glamorous geometry of the city's boulevards. Franz Kafka sensed this, noting in his journal: “The Métro furnishes the best opportunity for the foreigner to imagine that he has understood, quickly and correctly, the essence of Paris.”

I remember first arriving in Paris in 1990 from Berlin -- where the U-Bahn trains were brightly lit, spacious and run on the honor system -- to find myself trapped in a narrow, dusky cage full of cutting glances and sophisticated, corrupt odors, and wondering whether I was ready to handle such a sensual, dangerous environment. Clochards (panhandlers) formed intimidating gypsy camps on banks of bucket-bottomed plastic chairs, clotting the circulation with their impedimenta of mongrels and plastic liter bottles of red wine, performing unscripted drunken operettas for passers-by. Even the many remaining Hector Guimard Métro entrances, with their glaucous wrought-iron stanchions clutching balefully glowing orangish-red balls, looked as suggestively bulbous as the pistils and stamens of alien orchids.

If this was what passed for public art in Paris, I reflected, the mores of the Parisian public were bound to be interesting.

What legends of Métro history I could glean only reinforced this impression, making the vaulted roofs of hygienic white tile seem like a coating of soothing whitewash over ulcerous cavities. I learned that a 1903 fire in a train in the Couronnes station had claimed 84 lives, as passengers who remained too long on the platform demanding refunds for their 3-sous tickets were asphyxiated -- briefly leading the system to be dubbed the '“Necropolitain.” (The same ill-starred station shook under a 1916 Zeppelin attack, which caused a tunnel roof to collapse seconds after a train had passed.)

When the Seine overflowed its banks -- the highwater mark can still be seen in lines marked “1910” on the sides of Latin Quarter buildings -- employees were forced to paddle between inundated stations on rafts. During the Occupation, when Jews were forced to wear yellow stars and ride in the last car, nicknamed the “Synagogue,” the Metro became a meeting place for the Resistance, feared by German soldiers.

The Metro is also an ossuary of forgotten technology: it was partly conceived, after all, by the same engineer, Jean-Baptiste Bérlier, who invented the magnificent pneumatique network, a public mail system that sent rubber-tipped containers, driven by compressed air, rocketing through tubes beneath the streets. It included the gravity-operated funicular of Montmartre, an incline railway whose descending car, weighted down by water, served as a counterweight for its simultaneously ascending counterpart. And it almost became a proving ground for one of the most revolutionary transit technologies of the last century.

The Aramis system would have allowed commuters to order tiny individual subway cars, seating only 5 to 10 passengers, to stations near their homes; the lightweight compartments, feeding from branch lines onto a central track, would have assembled into trainlike lines as they approached the center of Paris. There were working models by 1987, but the system was finally killed, in part by political in-fighting. The whole story is told by Bruno Latour in his fascinating book-length essay Aramis, or the Love of Technology.

If I could lead an unofficial tour of the Parisian Metro, it would include not only such forgotten history but also the sensual highlights the designers of the 21st-century Metro will never be able to capture -- and, one hopes, will never succeed in fully eliminating.

The smells, for example: that sulfuric, rotten egg-and-Camembert odor in the R.E.R. tunnel between Châtelet and the Gare du Nord. The sounds: the rural stridulations of the chorus of crickets that live beneath the friction-heated rails in the St.-Augustin station, matched by the urbane “pardons” of the rush-hour commuters whose paths cross in bustling stations like République. The sensation of ducking beneath the dragonflylike glass wings of the Art Nouveau Abbesses station entrance in Montmartre, and corkscrewing down the spiral staircase that plunges to the platforms 40 yards underground (only to encounter a cordon of ticket-inspectors trapping dizzy fare-skippers at the bottom). The fleeting glimpse of posters for ancient aperitifs in phantasmagoric ghost stations, like Croix-Rouge, on Line 10, and St.-Martin, on Line 8, closed during the Second World War and never reopened.

And best, most fleeting of all, the intoxication of a lingering sideways glance across a pane of safety glass, as a dark-eyed stranger disappears -- drawn backward into a tunnel, and forever out of your life -- as you walk, half regretful, half relieved, toward the exit.

-FIN-

Full disclosure: This is a modified version of something I wrote 20 years ago, when my style—influenced by years of immersion in the French decadents—was, let’s say, un petit peu plus baroque. But I enjoyed revisiting a formative period, and place, in my life; I hope you enjoyed following me beneath the pavés.