Straphangers in Manhattan

An Update on the State of Transit in NYC

It had been a while since I'd taken a pleasure trip to New York City—not since before the pandemic, in fact. I'd gone there on a couple of research trips immediately prior to Covid, but my wife hadn't been particularly interested in vacationing south of the Canadian border when Trump was in the White House, which I understood. In the meantime, though, the legend of the Big Apple has been growing in our children's minds—Times Square! the Statue of Liberty! the Empire State Building!—so we arranged a 48-hour getaway for their spring break. (November is going to be upon us sooner than we think.)

You know me. Driving isn't on the table; as a rule, where there's a train, I try to take it. But the last time I took the Adirondack from Montreal to New York, it took 13 hours—all of them daylight hours. (Taking the train from Montreal to Toronto, which is about the same distance, takes under five hours.) In other words, for two days in Manhattan, you'd have to budget four days in total. In more civilized times, I'm told, a train left from Montreal's Windsor Station at night, and got you into Manhattan the following morning, after a pleasant sleep in a Pullman.

I believe the technical term for the situation, as it exists today, is "idiotic."

So we cashed in some airline miles, bought carbon credits (I know, I know, but better than doing nothing), and caught an early-morning flight due south, paralleling the Hudson. I prefer arriving at Newark, in New Jersey, because you can catch the train at the airport; arriving at LaGuardia means wrestling your luggage onto a bus, then the subway, and showing up in Manhattan flustered and pre-ruffled; the alternative is a very expensive taxi ride. But the transfer was a little less slick than I remembered. We had to wait outside Terminal A for a shuttle bus to the Airtrain, the airport monorail, which took us on a slow, shaky ride from one end of the line, through five stations, to deposit us at the RailLink Station. Perhaps because it was a Sunday, we endured a half-hour wait in a crowded, glassed-in waiting room on the platform before boarding an NJ Transit bi-level commuter train, which was, late, and featured standing-room only for the half-hour or so ride into Penn Station. From my entourage: grumbling and sarcastic comments about the "convenience" of Newark, and time wasted in transit that could have been spent in Manhattan.

This is one of the world's great cities, population: 8.5 million. Yet at a time when even second-tier airports in Asia are served by high-speed rail, New York still hasn't gotten around to building a decent rail link from its three major airports to Manhattan.

All right, I'll stop right there. I don't want this to turn into a Thomas Friedman-style lament about the weakness of North American infrastructure. (Besides, I've whinged about passenger rail on this continent enough in previous posts, including this one.) We fully intended to not get discouraged, and ride a transit network that had stood the test of time: the New York Subway.

My wife and I had read the articles, and talked to friends who'd made similar trips: the subway, according to these reports, wasn't as safe it was before the pandemic. When we told the American customs and border officer in Montreal's airport where we were headed, he went off on a tirade about staying off the subway with kids after dark; he boasted about he and a friend ejecting a drunken homeless man from a subway car. (Typical of the enforcement mentality: If you think you're a hammer, you're always looking for a nail to hit on.) The implication: these days, you best be on your toes, buddy.

As a life-long transit rider, I've learned to take these warnings with a grain of salt. From Mexico City to Moscow, I've found that there's an easy way to deal with tense situations in transit: you can just move away—to somewhere else on the platform, or to the other end of the bus or the train. If you are stuck, for example in a metro without an open-gangway (which allows you to walk between cars), you have the choice to get off at the next stop. In a lifetime of riding, though, I've never actually been assaulted. When I think about it, my closest brushes with death have been when I've gotten into a taxi or jitney with an incompetent, inebriated, or larcenous driver. Then I've really felt trapped.

Also, in big cities, shit happens. How could it not? Cities are filled with millions of humans, and we're a fantastically unpredictable species. The amazing thing is that shit doesn't go down much more often.

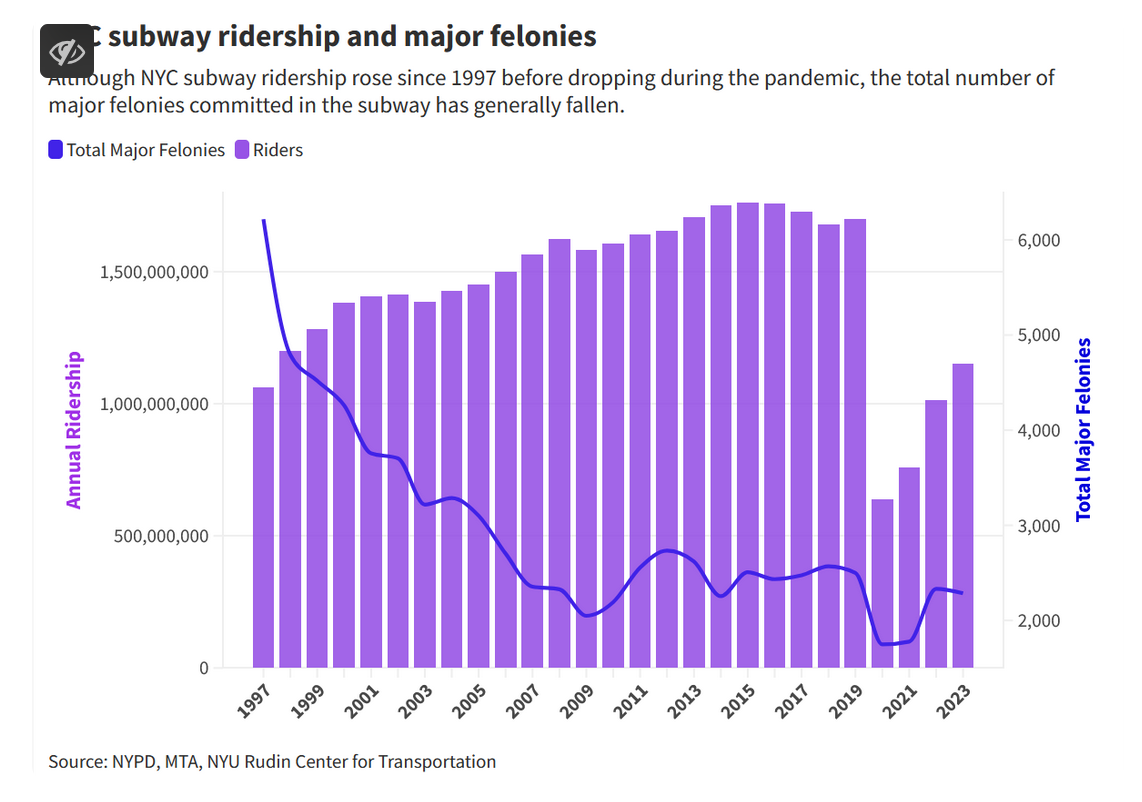

(Excuse this fact-baked digression, but when you dig down into the details, the subway seems to be getting safer as time goes on. According to the MTA and the NYPD, ridership is recovering from post-pandemic levels, while, if anything, felonies are below 2019 levels...

...End of digression.)

Maybe we got lucky, but our transit-riding experience on this trip was hassle-free.* We got a sweetheart deal on a hotel on an aromatic stretch of West 28th Street where the sidewalks are filled with the overflow from wholesale flower shops; the No. 1 train was half a block to the west, and to the east, a five-minute walk would put us on the B or D trains uptown, or the F train to Brooklyn.

One thing has changed since my last visit: there are now credit-card readers at the turnstiles, which means you can just tap your card, and it's automatically charged. By reflex, I'd gone to a machine and bought a Metrocard, for which you're charged a buck. Turns out this is no longer necessary—in fact, it's cheaper to tap your credit card. (Even compared to a 7-day Metrocard: you can start with your Visa, AmEx, or Mastercard any day, and after your 12th ride, all subsequent rides that week are free.) Oh well: now I have a blue-and-yellow souvenir card in my wallet.

It was interesting to ride the subway with my boys, who are 12 and 7—soon to be 8, —years old. They're pretty jaded straphangers, old hands on the Montreal metro, familiar with Toronto's subway, and they've already experienced European systems, including Paris and Rome's. But the express trains were new to them—in between stations, Desmond was surprised to see a train on the middle track gaining on us, bobbing by, and then flashing onwards into the gloom. They weren't intimidated by the noise or the crowds; in fact, we had to restrain them from racing ahead, and getting lost in the tunnels.

But I'm pretty sure they were impressed by Grand Central Terminal. Desmond recognized the clock at the center of the station from the opening of Saturday Night Live; Victor stared up with gratifying awe at the turquoise ceiling, a-glitter with golden constellations. (Arriving in Penn Station, of course, elicited no awe; just a rapid search for the exit.) And they loved a lesser-touristed aspect of the transit system of this archipelago-metropolis: the NYC Ferries. Rather than devoting half a day to the Statue of Liberty, they did a drive-by—or sail-by—on the Staten Island ferry.

Then, after walking across the Brooklyn Bridge, we walked down to the Dumbo ferry terminal, where for $4 (adults, Victor rode free), we got two-hours worth of rides on the public system: six routes, 25 piers, to all five boroughs—in fact, you can ride all the way to Rockaway Beach, if you're longing for some Atlantic surf. And the ferries are fast: the ones we rode, first to Wall Street, then up to the pier at 34th Street, seemed to keep pace with the car traffic on FDR Drive (turns out their top speed is 25 knots, or 46 km/h).

Forty-eight hours is not a long time. We were letting the kids call the shots, which meant that I didn't have a chance to do the things I otherwise might have, were I a solo-straphanger-on-the-loose (Those would have included a visit to the Moynihan Train Hall, the newish glass-roofed waiting room for Amtrak and LIRR trains next to Penn Station will be for the next visit, as will a ride on the M34 Select Bus along 34th Street, which is reportedly an improvement on the notoriously pokey crosstown bus service. Next time.) Which meant we walked, a lot. According to our smartphones, an average of 24,000 steps a day. And in spite of that, our kids, unlike their ready-to-drop parents, still had energy at the end of the day.

The car traffic is still awful enough. The congestion charge, which I wrote about here, has yet to go into effect: this traffic-limiting measure, which will force drivers to pay a $15 charge to enter Lower Manhattan, could go into effect on June 1 2024, and it might have a real impact on livability. (The plan still faces 6 lawsuits before it goes into effect, according to this article.)

Paul Theroux got it right when he visited the city back in 1982, a time when the subway was at a nadir in terms of security and reliability. "The subway is New York City’s best hope," he concluded in the pages of The New York Times Magazine, after a week riding the rails, and in spite of the muggings and brawls he'd witnessed. The private automobile has no future in this city whatsoever."

That remains just as true in 2024. As does the author's observation, which I was reminded of as I walked over the sidewalk grills on 6th Avenue, where, just beneath your feet, you can hear the No. 1 trains rattling uptown, as they have for 120 years.

"What is amazing," wrote Theroux, "is that back in 1904 a group of businessmen solved New York's transport problems for centuries to come. What an engineering marvel they eventually created in this underground railway!"

Amen. Long may it run.

- Two days after our visit, the Internet was alight with a scene of a horrific struggle in a northbound A-train in Brooklyn: smartphone footage shows passengers ducking as a man, who had been threatened by another passenger, disarmed him and shot him in the head, fatally. My thoughts are with the people on that train who had to live through this horrible, and likely traumatizing, event. That said, the subway carried 3.2 million other people that day, as it does every day of the year, incident-free.